How the West Misunderstands Iran’s Middle Class - Part 2

In a previous article, I examined a single paragraph from a piece by the respected Iranian-American scholar Abbas Milani, aiming to shed light on how the West continues to misread Iran’s middle class—a group that may, in fact, hold the key to shaping Iran’s, and by extension the Middle East’s, future trajectory.

This time, I turn to another paragraph from the same article. You do not need to have read my earlier piece or Milani’s original article to follow along, although doing so may provide useful context.

The paragraph under examination appears third from the bottom, under the heading Tehran, 1979, and Baghdad, 2003:

“Events in Iran in 1979, on the day of the revolution, provide a revealing point of contrast and comparison. For about a week, there was no police or security force in Tehran, then a city of some seven million inhabitants. On the night of the revolution, thousands of guns, pistols, and machine-guns had been ‘liberated’ from deserted barracks and distributed among the populace. Gun-toting youth, red or black bandannas on their heads, roamed the city. At Tehran University, a group of professors—of which I was one—decided to keep the university free from guns. We were each issued a simple armband, indicating that we were members of the faculty. We succeeded in keeping armed individuals out of the campus. Not a single act of vandalism took place in the university. In fact, throughout the city, there were no lynchings, no revenge murders, and only a handful of ransacked houses or buildings.”

Here, Milani continues to present the Iranian middle class as a largely homogeneous entity, deeply aligned with Western moral codes and civic ideals. In the paragraph immediately preceding the one quoted above—not included here—he primes the reader by contrasting the post-Saddam chaos in Iraq, where the breakdown of civil order is attributed to the absence of a true middle class, with the supposed restraint demonstrated by Iranians in 1979. His observations about Iraq are largely well-founded and supported by available evidence.

However, his portrayal of the Iranian Revolution edges towards an almost utopian depiction—one that few, if any, serious historians—or Iranians—would recognise. It is unclear whether Milani refers strictly to the day of the revolution itself and the week that followed, or to the broader sequence of events before and after. Either way, the documented history of 1979 Iran stands in sharp contrast to the idyllic version he presents.

To begin with, the Iranian Revolution was—unsurprisingly—violent. If you are not familiar with the historical record, I recommend consulting this Associated Press archival footage, which captures the final days leading up to the revolution and its immediate aftermath. Then compare that with Milani’s assertion: “In fact, throughout the city, there were no lynchings, no revenge murders, and only a handful of ransacked houses or buildings.”

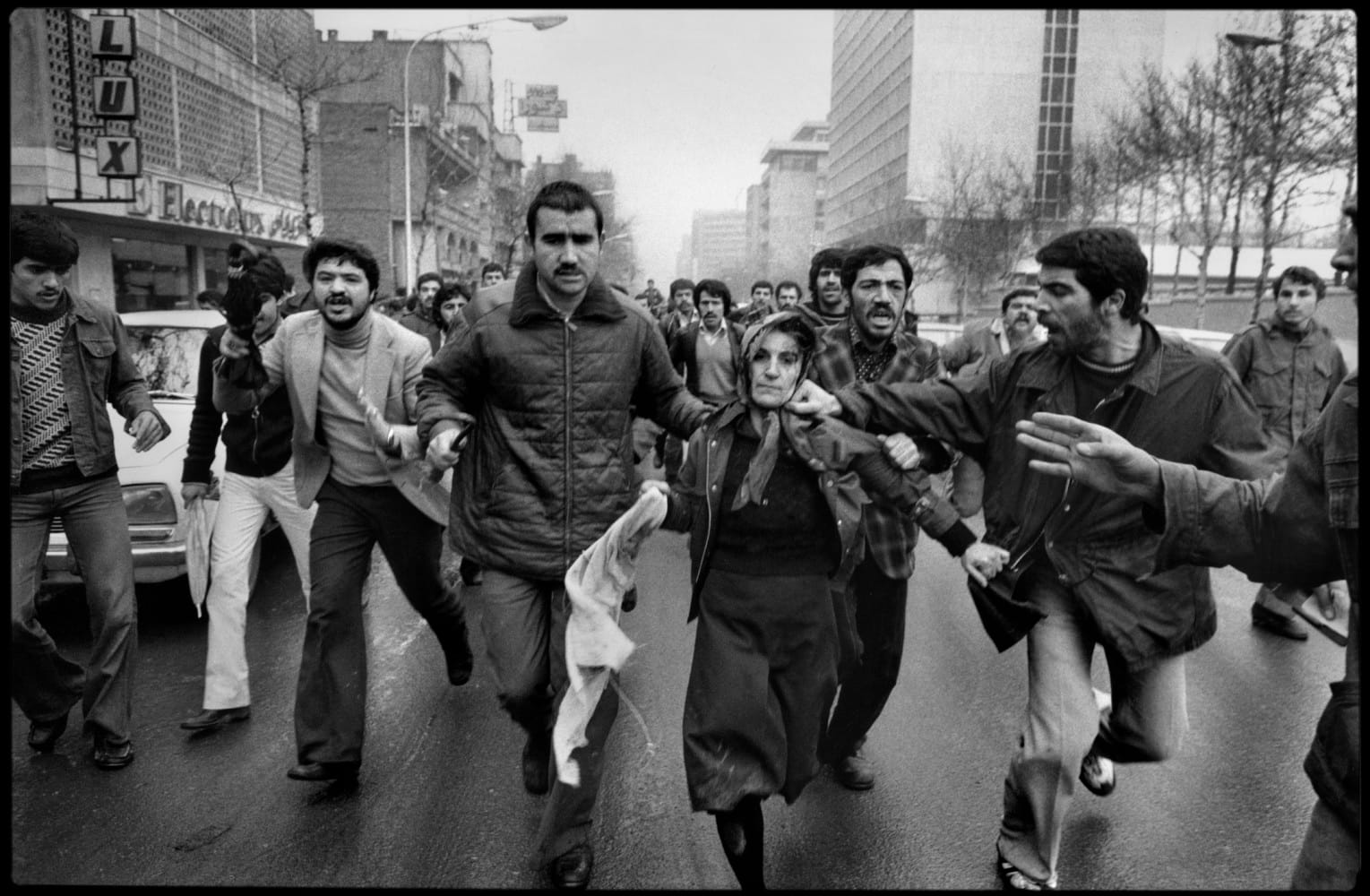

Photo: After a demonstration at the Amjadiyeh Stadium in support of the Constitution and of Shapour Bakhtiar, who was appointed Prime Minister by the Shah before he left the country, a woman, believed to be a supporter of the Shah is mobbed by a revolutionary crowd. Tehran, Iran. January 25, 1979. Photo by Abbas Attar.

The photo above was taken about two weeks before the final victory. Look closely—can you sense the tension? What do you think happened to the woman pictured? Was she treated humanely, given a fair trial for whatever accusations—perhaps supporting the Shah—were made against her?

Such incidents were not isolated. Consider the next photograph, taken on the day of the revolution itself:

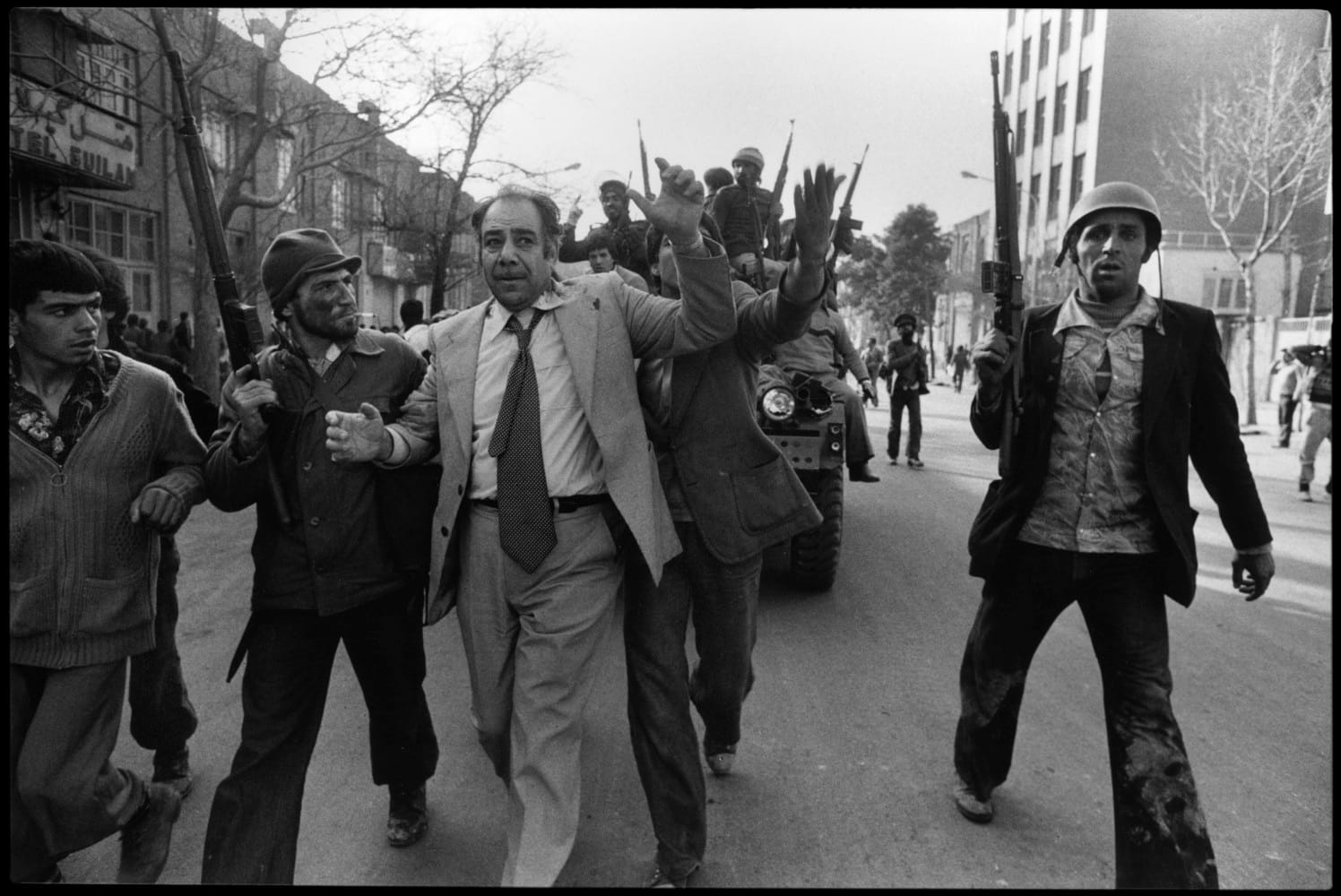

Photo: Armed revolutionary mob takes away a presumed member of the SAVAK secret police on the day of the victory of the Revolution. IRAN. Tehran. February 11th 1979. Photo by Abbas Attar.

The man depicted is allegedly an employee of SAVAK, the Shah’s notorious secret police. It is well documented that senior members of SAVAK were executed swiftly after the revolution. Within days, hundreds of others were imprisoned or executed without anything resembling due process. Of the first 200 executions following the revolution, it is believed that approximately 80% were former SAVAK employees.

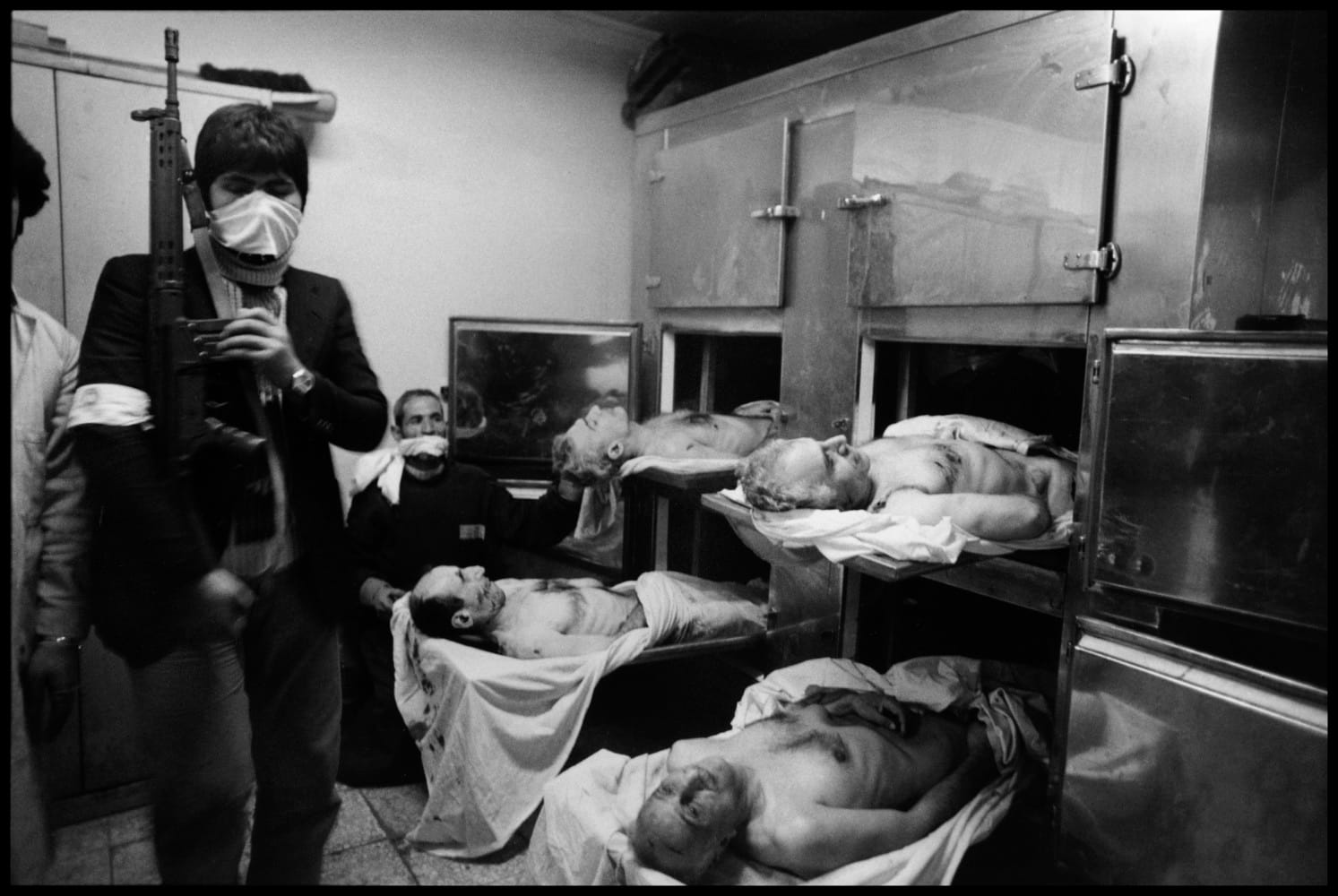

Photo: The bodies of four generals, executed after a secret trial held at Ayatollah KHOMEINY's headquarters, at the Refa girls' school. Their bodies lie at the morgue. Top left General KHOSROWDAD, top right General RAHIMI, bottom left General NAJI, bottom right General NASSIRI (ex chief of the SAVAK secret police). IRAN. Tehran. February 15th, 1979. Photo by Abbas Attar.

But what about vandalism and destruction? Did the revolutionaries—the same Iranian middle class that Milani praises—refrain from targeting public property?

I encourage you to examine the following images and decide for yourself:

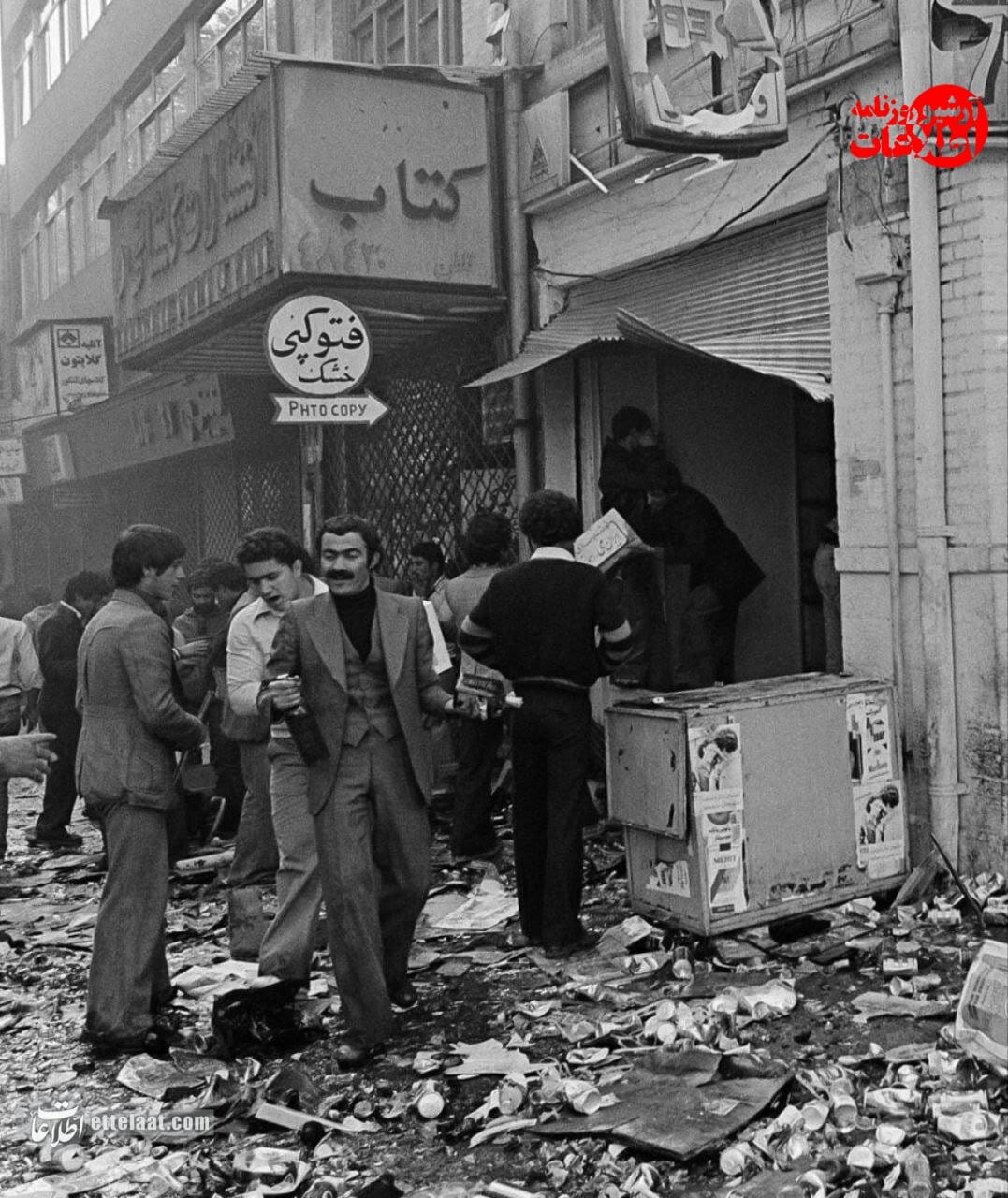

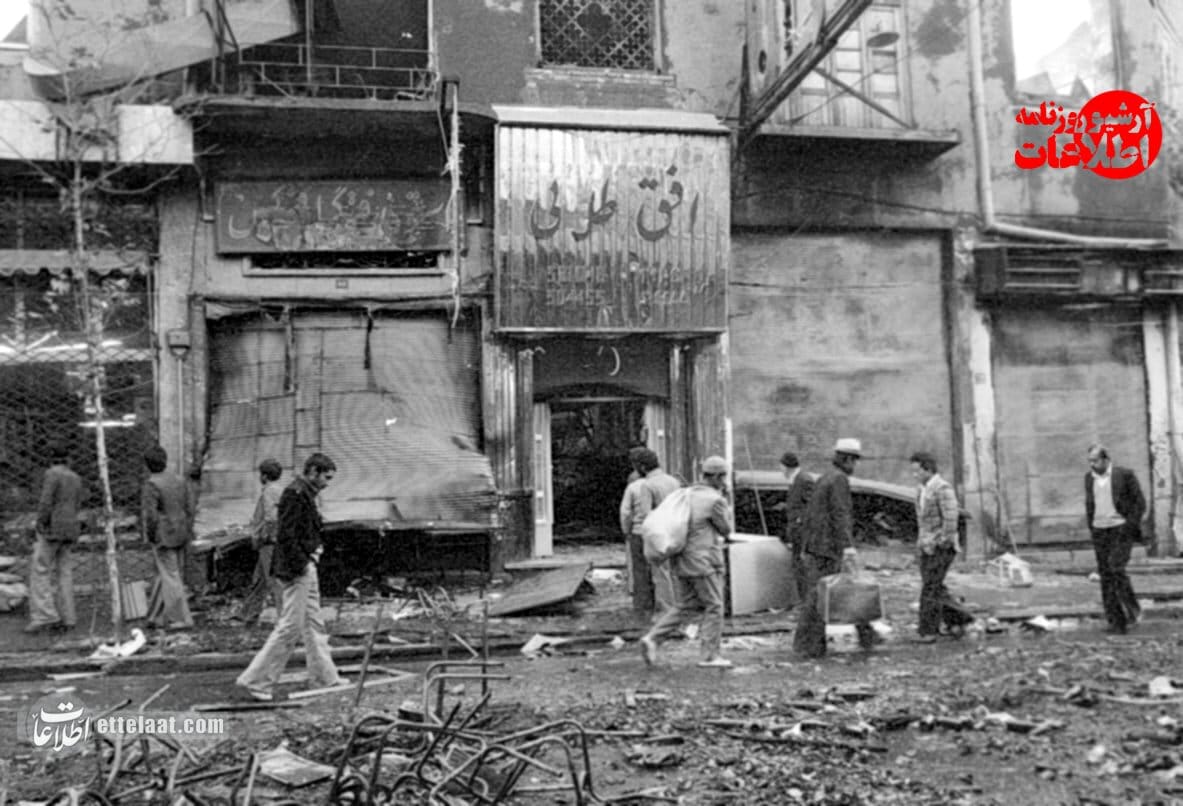

Photo: Demonstrators loot government bureaus and banks as well as liquor shops, cabarets and cinemas during the Revolution in Tehran, 4th November 1978. Documents thrown out of the buildings are spread on the street while furniture is set ablaze. Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images.

Photo: The aftermath of a day of demonstrations and looting in Shah Reza Avenue, during the Revolution in Tehran, 4th November 1978. The rioters stand in front of a heap of burnt government and bank documents in the street. Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images.

Photo: Demonstrators attack and loot the El Al Israeli Airlines offices in Tehran, 4th November 1978. Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images.

One might reasonably argue that much of the early destruction was directed against property seen as belonging to the Shah or his appointed government. In the charged atmosphere of a revolution, such acts—however regrettable—are almost to be expected. But according to Milani’s portrayal, the Iranian middle class should have demonstrated something different once the dust had settled. After all, this was the very group he credits with embodying many Western democratic values. Surely, then, they would refrain from vandalising the property of their fellow citizens—those not directly tied to the previous regime?

And yet, that is not what transpired.

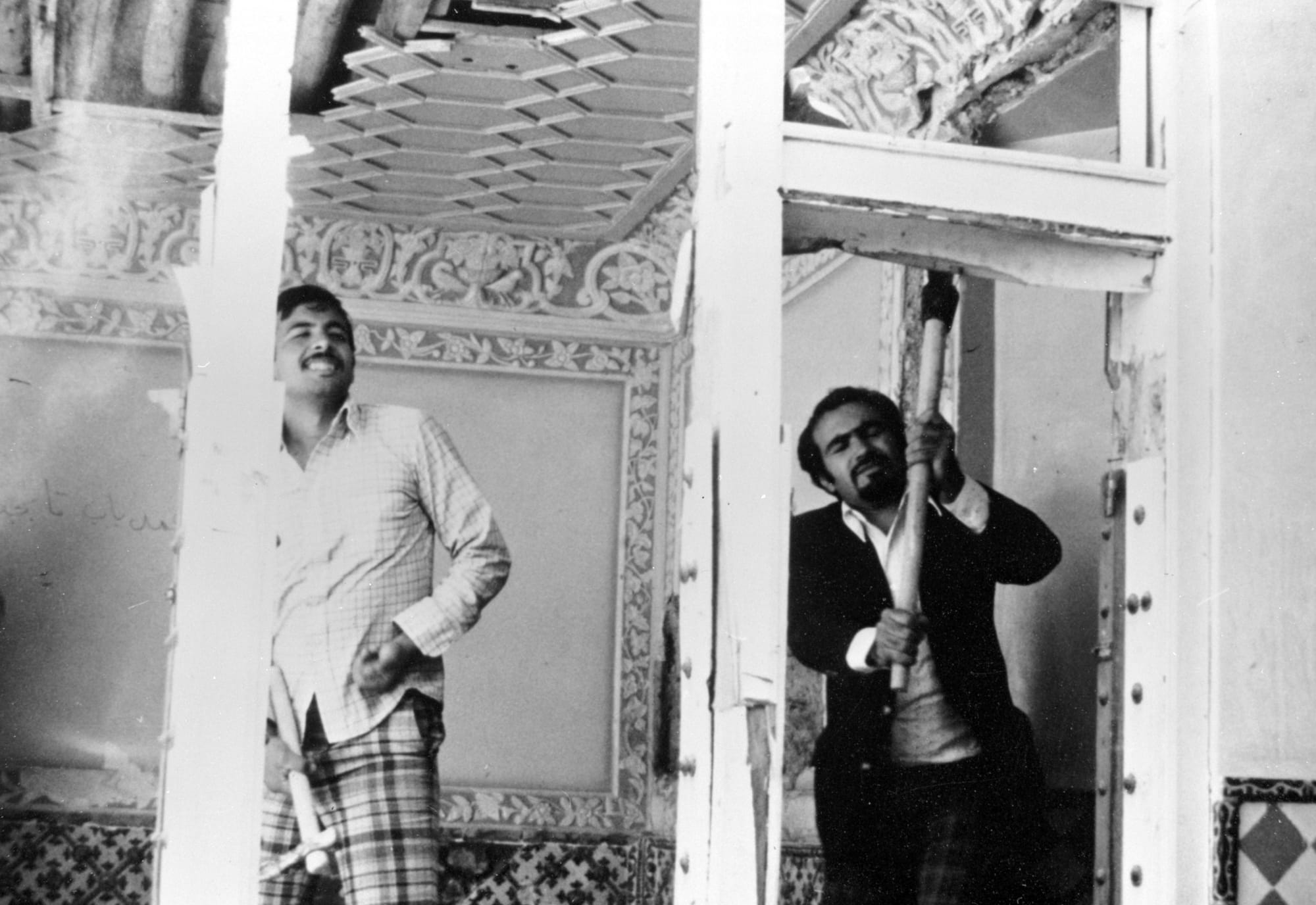

The destruction persisted, particularly targeting anything seen as incompatible with emerging Islamic values. Liquor stores and alcohol factories were among the first to fall victim.

Nor were religious minorities spared. The House of the Báb in Shiraz—a historic and cultural site for Iran’s Bábí and Baháʼí communities—was deliberately destroyed. Irrespective of one’s religious leanings, this was a loss to Iran’s historical and cultural heritage: it was the location where the Báb first proclaimed his mission.

Thus, we are faced with a fundamental question: what are we to believe about 1978–79 Iran?

Is—or was—the Iranian middle class as Milani portrays it: an orderly, enlightened force standing as the West’s natural ally? Or is this yet another romanticised image, crafted for Western consumption by those eager to see Iran through a particular lens?

It is easy to blame the darker aspects of the revolution on “the fundamentalist” or “the extremist”, and to credit everything else to the true middle class. Yet the reality is that the lines were blurry back then, and to some extent, they remain blurred even today.

For example, many Iranians did consume alcohol at the time—presumably including those who would not have taken part in vandalising liquor stores—a significant portion of whom considered themselves no less Muslim than those who abstained. This remains true today. Does that place them firmly within the middle class Milani describes—the pure, enlightened force supposedly primed for democratic governance? Would that be sufficient to bring democracy to Iran, which is, in essence, the central point of Milani’s argument?

Are Iranians truly ready to allow everyone a voice in a genuine democracy—including religious minorities, or political views many might regard as absurd, idiotic, or outright dangerous?

There are many concerns and questions of this kind that demand careful attention—and far more evidence exists, beyond the few photos shown above, demonstrating how much groundwork is still needed before serious conversations about democracy in Iran can truly begin. What is shown above merely scratches the surface; across Iran’s social fabric, historical memory, and political culture, countless other examples could be found, each pointing to the same underlying reality.

Certainly, people are tired, frustrated, and under immense pressure. But frustration alone does not automatically make one a supporter of democracy, nor does repeating the word “democracy” necessarily lead to a real understanding of its attributes, demands, and implications.

Iranian society should neither be caricatured as a backward, alien culture, nor romanticised as a democracy-in-waiting, perfectly mirroring Western ideals.

To grasp Iran properly requires an open mind, intellectual humility, and a sincere commitment to understanding its complexities—so that, in time, it may be helped to achieve what it genuinely needs for a better future.

Unfortunately, articles like Milani’s—however well-intentioned—are no substitute for such genuine understanding.